Lines

| Staff or stave The fundamental latticework of music notation, upon which symbols are placed. The five staff lines and four intervening spaces correspond to pitches of the diatonic scale - which pitch is meant by a given line or space is defined by the clef. With treble clef, the bottom staff line is assigned to E above middle C (E4 in note-octave notation); the space above it is F4, and so on. The grand staff combines bass and treble staffs into one system joined by a brace. It is used for keyboardand harp music. The lines on a basic five-line staff are designated a number from one to five, the bottom line being the first one and the top line being the fifth. The spaces between the lines are, in the same fashion, numbered from one to four. In music education, for the Treble Clef, the mnemonic "Every Good Boy Does Fine" (or "Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge") is used to remember the value of each line from bottom to top. The interstitial spaces are often remembered as spelling the word "face" (notes F-A-C-E). |

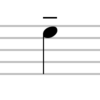

| Ledger or leger lines Used to extend the staff to pitches that fall above or below it. Such ledger lines are placed behind the note heads, and extend a small distance to each side. |

| Bar line Used to separate measures (see time signatures below for an explanation of measures). Bar lines are extended to connect the upper and lower staffs of a grand staff. |

| Double bar line, Double barline Used to separate two sections or phrases of music. Also used at changes in key signature or major changes in style or tempo. A bold double bar line indicates the conclusion of a movement or an entire composition. |

| Dotted bar line, Dotted barline Subdivides long measures into shorter segments for ease of reading, usually according to natural rhythmic subdivisions. |

| Accolade, brace Connects two or more lines of music that are played simultaneously.[1] Depending on the instruments playing, the brace, or accolade, will vary in designs and styles. |

[edit]Clefs

Main article: Clef

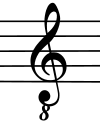

Clefs define the pitch range, or tessitura, of the staff on which it is placed. A clef is usually the leftmost symbol on a staff. Additional clefs may appear in the middle of a staff to indicate a change in register for instruments with a wide range. In early music, clefs could be placed on any of several lines on a staff.

| G clef (Treble Clef) The centre of the spiral defines the line or space upon which it rests as the pitch G above middle C, or approximately 392 Hz. Positioned here, it assigns G above middle C to the second line from the bottom of the staff, and is referred to as the "treble clef." This is the most commonly encountered clef in modern notation, and is used for most modern vocal music. Middle-C is the 1st ledger line below the stave here. The shape of the clef comes from a stylised upper-case-G. |

| C clef (Alto Clef and Tenor Clef) This clef points to the line (or space, rarely) representing middle C, or approximately 262 Hz. Positioned here, it makes the center line on the staff middle C, and is referred to as the "alto clef." This clef is used in modern notation for the viola. While all clefs can be placed anywhere on the staff to indicate various tessitura, the C clef is most often considered a "movable" clef: it is frequently seen pointing instead to the fourth line and called a "tenor clef". This clef is used very often in music written for bassoon, cello, and trombone; it replaces the bass clef when the number of ledger lines above the bass staff hinders easy reading. C clefs were used in vocal music of the classical era and earlier; however, their usage in vocal music has been supplanted by the universal use of the treble and bass clefs. Modern editions of music from such periods generally transpose the original C-clef parts to either treble (female voices), octave treble (tenors), or bass clef (tenors and basses). |

| F clef (Bass Clef) The line or space between the dots in this clef denotes F below middle C, or approximately 175 Hz. Positioned here, it makes the second line from the top of the staff F below middle C, and is called a "bass clef." This clef appears nearly as often as the treble clef, especially in choral music, where it represents the bass and baritone voices. Middle C is the 1st ledger line above the stave here. The shape of the clef comes from a stylised upper-case-F (which used to be written the reverse of the modern F) |

| Neutral clef Used for pitchless instruments, such as some of those used for percussion. Each line can represent a specific percussion instrument within a set, such as in a drum set. Two different styles of neutral clefs are pictured here. It may also be drawn with a separate single-line staff for each untuned percussion instrument. |

| Octave Clef Treble and bass clefs can also be modified by octave numbers. An eight or fifteen above a clef raises the intended pitch range by one or two octaves respectively. Similarly, an eight or fifteen below a clef lowers the pitch range by one or two octaves respectively. A treble clef with an eight below is the most commonly used, typically used instead of a C clef for tenor lines in choral scores. Even if the eight is not present, tenor parts in the treble clef are understood to be sung an octave lower than written. |

Tablature

For guitars and other plucked instruments it is possible to notate tablature in place of ordinary notes. In this case, a TAB-sign is often written instead of a clef. The number of lines of the staff is not necessarily five: one line is used for each string of the instrument (so, for standard 6-stringed guitars, six lines would be used). Numbers on the lines show on which fret the string should be played. This Tab-sign, like the Percussion clef, is not a clef in the true sense, but rather a symbol employed instead of a clef. The interstitial spaces on a tablature are never used.

For guitars and other plucked instruments it is possible to notate tablature in place of ordinary notes. In this case, a TAB-sign is often written instead of a clef. The number of lines of the staff is not necessarily five: one line is used for each string of the instrument (so, for standard 6-stringed guitars, six lines would be used). Numbers on the lines show on which fret the string should be played. This Tab-sign, like the Percussion clef, is not a clef in the true sense, but rather a symbol employed instead of a clef. The interstitial spaces on a tablature are never used.

[edit]Notes and rests

Main article: Note value

Note and rest values are not absolutely defined, but are proportional in duration to all other note and rest values. The whole note is the reference value, and the other notes are named (in American) in comparison; i.e. a quarter note is a quarter the length of a whole note.

| Note | British name / American name | Rest |

| Breve / Double whole note |  |

| Semibreve / Whole note |  |

| Minim / Half note |  |

| Crotchet / Quarter note | |

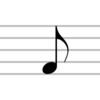

| Quaver / Eighth note For notes of this length and shorter, the note has the same number of flags (or hooks) as the rest has branches. |  |

| Semiquaver / Sixteenth note |  |

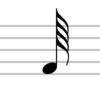

| Demisemiquaver / Thirty-second note |  |

| Hemidemisemiquaver / Sixty-fourth note |  |

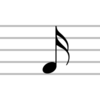

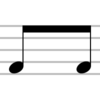

| Beamed notes Beams connect eighth notes (quavers) and notes of shorter value, and are equivalent in value to flags. In metered music, beams reflect the rhythmic grouping of notes. They may also be used to group short phrases of notes of the same value, regardless of the meter; this is more common in ametrical passages. In older printings of vocal music, beams are often only used when several notes are to be sung to one beat; modern notation encourages the use of beaming in a consistent manner with instrumental engraving, and the presence of beams or flags no longer informs the singer. Today, due to the body of music in which traditional metric states are not always assumed, beaming is at the discretion of the composer or arranger and irregular beams are often used to place emphasis on a particular rhythmic pattern. | |

| Dotted note Placing dots to the right of the corresponding notehead lengthens the note's duration. n dots lengthen the note by  its value, e.g. one dot by one-half, two dots by three-quarters, three dots by seven-eighths, and so on. Rests can be dotted in the same manner as notes. For example, if a quarter note had one dot alongside itself, it would get one and a half beats. its value, e.g. one dot by one-half, two dots by three-quarters, three dots by seven-eighths, and so on. Rests can be dotted in the same manner as notes. For example, if a quarter note had one dot alongside itself, it would get one and a half beats. | |

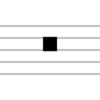

| Multi-measure rest Indicates the number of measures in a resting part without a change in meter, used to conserve space and to simplify notation. Also called "gathered rest" or "multi-bar rest". | |

Durations shorter than the 64th are rare but not unknown. 128th notes are used by Mozart and Beethoven; 256th notes occur in works of Vivaldi and even Beethoven. An extreme case is the Toccata Grande Cromatica by early-19th-century American composer Anthony Phillip Heinrich, which uses note values as short as 2,048ths; however, the context shows clearly that these notes have one beam more than intended, so they should really be 1,024th notes.

The name of very short notes can be found with this formula: Name = 2(number of flags on note + 2)th note.

[edit]Breaks

| Breath mark In a score, this symbol tells the performer to take a breath (or make a slight pause for non-wind instruments). This pause usually does not affect the overall tempo. For bowed instruments, it indicates to lift the bow and play the next note with a downward (or upward, if marked) bow. | |

| Caesura Indicates a brief, silent pause, during which time is not counted. In ensemble playing, time resumes when so indicated by the conductor or leader. | |

[edit]Accidentals and key signatures

Main articles: Accidental (music) and Key signature

[edit]Common accidentals

Accidentals modify the pitch of the notes that follow them on the same staff position within a measure, unless cancelled by an additional accidental.

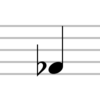

| Flat Lowers the pitch of a note by one semitone. |

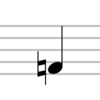

| Sharp Raises the pitch of a note by one semitone. |

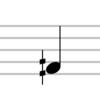

| Natural Cancels a previous accidental, or modifies the pitch of a sharp or flat as defined by the prevailing key signature (such as F-sharp in the key of G major, for example). |

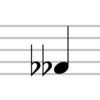

| Double flat Lowers the pitch of a note by two chromatic semitones. Usually used when the note to be modified is already flatted by the key signature. |

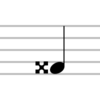

| Double sharp Raises the pitch of a note by two chromatic semitones. Usually used when the note to be modified is already sharped by the key signature. |

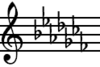

[edit]Key signatures

Key signatures define the prevailing key of the music that follows, thus avoiding the use of accidentals for many notes. If no key signature appears, the key is assumed to be C major/A minor, but can also signify a neutral key, employing individual accidentals as required for each note. The key signature examples shown here are described as they would appear on a treble staff.

[edit]Quarter-tone accidentals

These are examples of the most common notation for music involving quarter tones. (Microtonal notation in Western music is not widely standardized and other symbols may be used instead of the ones below.)

| Demiflat Lowers the pitch of a note by one quarter tone. (Another notation for the demiflat is a flat with a diagonal slash through its stem. In systems where pitches are divided into intervals smaller than a quarter tone, the slashed flat represents a lower note than the reversed flat.) |

| Flat-and-a-half (sesquiflat) Lowers the pitch of a note by three quarter tones. |

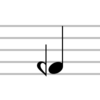

| Demisharp Raises the pitch of a note by one quarter tone. |

| Sharp-and-a-half Raises the pitch of a note by three quarter tones. Occasionally represented with two vertical and three diagonal bars instead. |

[edit]Time signatures

Main article: Time signature

Time signatures define the meter of the music. Music is "marked off" in uniform sections called bars or measures, and time signatures establish the number of beats in each. This is not necessarily intended to indicate which beats are emphasized, however. A time signature that conveys information about the way the piece actually sounds is thus chosen. Time signatures tend to suggest, but only suggest, prevailing groupings of beats or pulses.

| Specific time The bottom number represents the note value of the basic pulse of the music (in this case the 4 represents the crotchet or quarter-note). The top number indicates how many of these note values appear in each measure. This example announces that each measure is the equivalent length of three crotchets (quarter-notes). You would pronounce this as "Three Four Time", and was referred to as a "perfect" time. |

| Common time This symbol is a throwback to sixteenth century rhythmic notation, when it represented 2/4, or "imperfect time". Today it represents 4/4. |

| Alla breve or Cut time This symbol represents 2/2 time, indicating two minim (or half-note) beats per measure. Here, a crotchet (or quarter note) would get half a beat. |

| Metronome mark Written at the start of a score, and at any significant change of tempo, this symbol precisely defines the tempo of the music by assigning absolute durations to all note values within the score. In this particular example, the performer is told that 120 crotchets, or quarter notes, fit into one minute of time. Many publishers precede the marking with letters "M.M.", referring to Maelzel's Metronome. |

[edit]Note relationships

| Tie Indicates that the two (or more) notes joined together are to be played as one note with the time values added together. To be a tie, the notes must be identical; that is, they must be on the same line or the same space; otherwise, it is a slur (see below). |

| Slur Indicates that two or more notes are to be played in one physical stroke, one uninterrupted breath, or (on instruments with neither breath nor bow) connected into a phrase as if played in a single breath. In certain contexts, a slur may only indicate that the notes are to be played legato; in this case, rearticulation is permitted. Slurs and ties are similar in appearance. A tie is distinguishable because it always joins exactly two immediate adjacent notes of the same pitch, whereas a slur may join any number of notes of varying pitches. A phrase mark (or less commonly, ligature) is a mark that is visually identical to a slur, but connects a passage of music over several measures. A phrase mark indicates a musical phrase and may not necessarily require that the music be slurred. |

| Glissando or Portamento A continuous, unbroken glide from one note to the next that includes the pitches between. Some instruments, such as the trombone, timpani, non-fretted string instruments, electronic instruments, and the human voice can make this glide continuously (portamento), while other instruments such as the piano or mallet instruments will blur the discrete pitches between the start and end notes to mimic a continuous slide (glissando). |

| Tuplet A number of notes of irregular duration are performed within the duration of a given number of notes of regular time value; e.g., five notes played in the normal duration of four notes; seven notes played in the normal duration of two; three notes played in the normal duration of four. Tuplets are named according to the number of irregular notes; e.g., duplets, triplets, quadruplets, etc. |

| Chord Several notes sounded simultaneously ("solid" or "block"), or in succession ("broken"). Two-note chords are called dyad; three-note chords are called triads. A chord may contain any number of notes. |

| Arpeggiated chord A chord with notes played in rapid succession, usually ascending, each note being sustained as the others are played. |

[edit]Dynamics

Main article: Dynamics (music)

Dynamics are indicators of the relative intensity or volume of a musical line.

Other commonly used dynamics build upon these values. For example "piano-pianissimo" (represented as 'ppp' meaning so softly as to be almost inaudible, and forte-fortissimo, ('fff') meaning extremely loud. In some European countries, use of this dynamic has been virtually outlawed as endangering the hearing of the performers.[2] A small "s" in front of the dynamic notations means "subito", and means that the dynamic is to be changed to the new notation rapidly. Subito is commonly used with sforzandos, but all other notations, most commonly as "sff" (subitofortissimo) or "spp" (subitopianissimo).

| Forte-piano A section of music in which the music should initially be played loudly (forte), then immediately softly (piano). |

Another value that rarely appears is niente, which means 'nothing'. This may be used at the end of a diminuendo to indicate 'fade out to nothing'.

[edit]Articulation marks

Articulations (or accents) specify how individual notes are to be performed within a phrase or passage. They can be fine-tuned by combining more than one such symbol over or under a note. They may also appear in conjunction with phrasing marks listed above.

| Staccato This indicates that the note is to be played shorter than notated, usually half the value, the rest of the metric value is then silent. Staccato marks may thus appear on notes of any value, thus shortening their actual performed duration without speeding up the music itself. |

| Staccatissimo Indicates a longer silence after the note (as described above), making the note very short. Usually applied to quarter notes or shorter. (In the past, this marking’s meaning was more ambiguous: it sometimes was used interchangeably with staccato, and sometimes indicated an accent and not staccato. These usages are now almost defunct, but still appear in some scores.) |

| Dynamic accent The note is played louder or with a harder attack than any surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. |

| Tenuto This symbol has several meanings. It usually indicates that it be played for its full value, or slightly longer. It may indicate a separate attack on the note, or may indicate legato, in contrast to the dot of staccato. Combining a tenuto with a staccato dot indicates a slightly detaching ("portato" or "mezzo staccato"). |

| Marcato The note is played much louder or with a much stronger attack than any surrounding unaccented notes. May appear on notes of any duration. Also called petit chapeau. |

| Left-hand pizzicato or Stopped note A note on a stringed instrument where the string is plucked with the left hand (the hand that usually stops the strings) rather than bowed. On the horn, this accent indicates a "stopped note" (a note played with the stopping hand shoved further into the bell of the horn). |

| Snap pizzicato On a stringed instrument, a note played by stretching a string away from the frame of the instrument and letting it go, making it "snap" against the frame. Also known as a Bartók pizzicato. |

| Natural harmonic or Open note On a stringed instrument, denotes that a natural harmonic is to be played. On a valved brass instrument, denotes that the note is to be played "open" (without lowering any valve, or without mute). In organ music, this denotes that a pedal note is to be played with the heel. |

| Fermata (Pause) An indefinitely-sustained note or chord. Usually appears over all parts at the same metrical location in a piece, to show a halt in tempo. It can be placed above or below the note. |

| Up bow or Sull'arco On a bowed string instrument, the note is played while drawing the bow upward. On a plucked string instrument played with a plectrum or pick (such as a guitar played pickstyle or a mandolin), the note is played with an upstroke. In organ notation, this marking indicates to play the pedal note with the toe. |

| Down bow or Giù arco Like sull'arco, except the bow is drawn downward. On a plucked string instrument played with a plectrum or pick (such as a guitar played pickstyle or a mandolin), the note is played with a downstroke. Also note in organ notation, this marking indicates to play the pedal note with the heel. |

[edit]Ornaments

Ornaments modify the pitch pattern of individual notes.

| Trill A rapid alternation between the specified note and the next higher note (according to key signature) within its duration. Also called a "shake." When followed by a wavy horizontal line, this symbol indicates an extended, or running, trill. In much music, the trill begins on the upper auxiliary note. |

| Mordent Rapidly play the principal note, the next higher note (according to key signature) then return to the principal note for the remaining duration. In much music, the mordent begins on the auxiliary note, and the alternation between the two notes may be extended. |

| Mordent (lower) Rapidly play the principal note, the note below it, then return to the principal note for the remaining duration. In much music, the mordent begins on the auxiliary note, and the alternation between the two notes may be extended. |

| Turn When placed directly above the note, the turn (also known as a gruppetto) indicates a sequence of upper auxiliary note, principal note, lower auxiliary note, and a return to the principal note. When placed to the right of the note, the principal note is played first, followed by the above pattern. A vertical line placed through the turn reverses the order of the auxiliary notes. |

| Appoggiatura The first half of the principal note's duration has the pitch of the grace note (the first two-thirds if the principal note is a dotted note). |

| Acciaccatura The acciaccatura is of very brief duration, as though brushed on the way to the principal note, which receives virtually all of its notated duration. |

[edit]Octaves

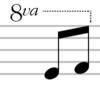

| Ottava alta Notes below the dashed line are played one octave higher than notated. |  | Ottava bassa Notes above the dashed line are played one octave lower than notated. |

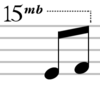

| Quindicesima alta Notes below the dashed line are played two octaves higher. |  | Quindicesima bassa Notes below the dashed line are played two octaves lower. The notation and dashed line are usually written below the staff, rather than above as shown here.[3] |

[edit]Repetition and codas

| Tremolo A rapidly-repeated note. If the tremolo is between two notes, then they are played in rapid alternation. The number of slashes through the stem (or number of diagonal bars between two notes) indicates the frequency at which the note is to be repeated (or alternated). As shown here, the note is to be repeated at a demisemiquaver (thirty-second note) rate. In percussion notation, tremolos are used to indicate rolls, diddles, and drags. Typically, a single tremolo line on a sufficiently short note (such as a sixteenth) is played as a drag, and a combination of three stem and tremolo lines indicates a double-stroke roll (or a single-stroke roll, in the case of timpani, mallet percussions and some untuned percussion instrument such as triangle and bass drum) for a period equivalent to the duration of the note. In other cases, the interpretation of tremolos is highly variable, and should be examined by the director and performers. |

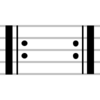

| Repeat signs Enclose a passage that is to be played more than once. If there is no left repeat sign, the right repeat sign sends the performer back to the start of the piece or the nearest double bar. |

| Simile marks Denote that preceding groups of beats or measures are to be repeated. In the examples here, the 1st usually means to repeat the previous bar, and the 2nd usually means to repeat the previous 2 bars. |

| Volta brackets (1st and 2nd endings, or 1st and 2nd time bars) Denote that a repeated passage is to be played in different ways on different playings. |

| Da capo Tells the performer to repeat playing of the music from its beginning. This is followed by al fine, which means to repeat to the word fine and stop, or al coda, which means repeat to the coda sign and then jump forward. |

| Dal segno Tells the performer to repeat playing of the music starting at the nearest segno. This is followed by al fine or al coda just as with da capo. |

| Segno Mark used with dal segno. |

| Coda Indicates a forward jump in the music to its ending passage, marked with the same sign. Only used after playing through aD.S. al coda or D.C. al coda. |

[edit]Instrument-specific notation

[edit]Guitar

The guitar has a right-hand fingering notation system derived from the names of the fingers in Spanish. They are written above, below, or beside the note to which they are attached. They read as follows:

| Symbol | Spanish | English |

|---|---|---|

| p | pulgar | thumb |

| i | índice | index |

| m | medio | middle |

| a | anular | ring |

| c, x, e, q, a | meñique | little |

[edit]Piano

[edit]Pedal marks

These pedal marks appear in music for instruments with sustain pedals, such as the piano, vibraphone and chimes.

| Engage pedal Tells the player to put the sustain pedal down. |

| Release pedal Tells the player to let the sustain pedal up. | |

| Variable pedal mark More accurately indicates the precise use of the sustain pedal. The extended lower line tells the player to keep the sustain pedal depressed for all notes below which it appears. The inverted "V" shape (/\) indicates the pedal is to be momentarily released, then depressed again. |

[edit]Other piano notation

| m.d. / MD / r.H./ r.h. / RH | mano destra (Italian) main droite (French) rechte Hand (German) right hand (English) |

| m.s. / MS / m.g./ MG / l.H. / l.h./ LH | mano sinistra (Italian) main gauche (French) linke Hand (German) left hand (English) |

| 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Finger identifications: 1 = thumb 2 = index 3 = middle 4 = ring 5 = little |